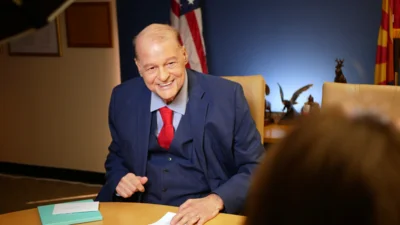

Arizona-based author and publisher Chris Buskirk said that embracing a culture of “smart, aggressive risk-taking” is one key to restoring America’s vitality.

“We need to be a risk-taking society if we want to be able to push forward on technological innovation, or if we want to maintain our position in the world,” Buskirk told host Leyla Gulen on The Grand Canyon Times Podcast. “If we want to maintain our national security, our personal security, those things all require risk.”

“We need to just embrace a culture of smart, aggressive, risk-taking,” Buskirk said.

Buskirk is publisher of American Greatness and author of the 2023 book, “America and the Art of the Possible: Restoring National Vitality in an Age of Decay.”

He made the topic of risk-taking the closing argument of his book, writing, “we need to recapture the frontier mindset that pulled us forward as a nation for much of our history.”

“A frontier is a challenging place full of unknown risks, a place where ingenuity and cooperation are necessary for survival,” Buskirk wrote. “When the American frontier closed, we became more risk-averse as well as more fractious and self-interested.”

In addition to being an author and publisher, Buskirk also has founded, built, and successfully sold multiple finance businesses including in insurance, reinsurance, specialty lending, and tax-credit financing. For more than 15 years he has been an investor in growth stages companies across the financial services space as well as in real estate, digital marketing, consumer brands, and media.

This full podcast episode also is available on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Full, unedited transcript of podcast episode -- Chris Buskirk on the Grand Canyon Times Podcast (August 6, 2023):

[00:00:00] Leyla Gulen: Welcome to the Grand Canyon Times podcast. I'm your host, Leyla Gulen. In this episode, we welcome our guest, Chris Buskirk. Chris founded, built and successfully sold multiple finance businesses including insurance, reinsurance, specialty lending, and more. For more than 15 years, he's been a successful investor in growth stages, companies across the financial services space.

[00:00:24] As well as real estate, digital marketing, consumer brands, and media crisps welcome. Thanks for having me, Leyla. Yeah. Congratulations on your new book. What's the title?

[00:00:35] Chris Buskirk: America And The Art of the Possible,

[00:00:38] Leyla Gulen: and it it goes on Restoring National Vitality in an Age of Decay. So let's start off here. Why did you decide to write this book?

[00:00:47] Chris Buskirk: I'll give you, I was thinking here like, do I want to give you the long version of the short version? I'll give you the, I'll give you the medium version of why this book. I've been thinking about the issues that I raised in the book for quite a while, which they're sort of [00:01:00] apparent, I think, in the title.

[00:01:01] What can We Do? What's Possible For America? And in the subtitle we talk about restoring vitality in the age of decay. And that's really the key to the way. I was thinking about the book before. It was a book just trying to cut, just trying to come up with something that I thought would be useful to people who read the book.

[00:01:22] And the original book I actually wrote is not the one that wound up being published because what I found was I got this book, I thought I, I wrote this manuscript that was about what was going wrong. Why is the middle class under pressure? Why has it been getting smaller and poorer for 50 years in this country?

[00:01:40] Why are lifespans in this country declining? They've been median life, expectancy's been declining for 10 or 12 years in America. There's all these, there's this sort of litany of complaints, political, cultural, spirituals, health wise, physical types of things, and everybody sort of knows them or has like an intuition about them.

[00:01:59] And so I, I [00:02:00] wrote this manuscript and what I found was, Having written like 200 pages, I thought, my God, all I did was complain. I thought like everybody, and it was like cathartic and it sort of felt good to be like, this is going wrong and that's going wrong and the other thing is going wrong. And I got to the end of it and I thought, this is like really, I.

[00:02:18] It's really not satisfying. It was sort of satisfying to write. It's not satisfying to read because it doesn't offer any solutions. All it is a bunch of problems. And yeah, I mean you talked about my background as an entrepreneur in the intro, and that's really sort of key to the way I approached the book That UL that I ultimately wrote was, which was to spend about the first half of the book.

[00:02:40] Describing the problems that, and quantifying the problems, making it very concrete. But the, the second half of the book is potential solutions, and that was the book I ultimately really wanted to write, which was how do we make the country better? And in a very concrete, Tangible because one of the things that I've been pretty [00:03:00] dissatisfied with with the political class is that they complain a lot, but then they don't actually offer solutions.

[00:03:06] They get people sort of all ginned up, like with fear and bloating or whatever, and then, but they're very short on solutions. And then as in. Entrepreneurial, you're the sort of fundamental thing that behind every entrepreneurial enterprise is you're solving a problem for somebody. And

[00:03:22] Leyla Gulen: without giving away the book too much, I'd love to hear what a couple of those solutions are.

[00:03:28] At least one of them maybe, but I. When did you decide that you wanted to write this book, at least the cathartic outpouring of your heart and soul call it complaining, but that cathartic moment, when did you start this process?

[00:03:42] Chris Buskirk: Yeah, I started thinking about it, so I had a book that came out in, well, I had one in 2016, and then another one in 2017.

[00:03:49] And so basically right after that I started to think, and those were more purely politically focused. Books. And I thought, and I, after that, I started thinking I wanna do something that was a little bit [00:04:00] different. And so I started really thinking about it, the, this, what became this book in 2017 and 18, and then getting really serious about it in, in 2019.

[00:04:09] I I, you won't be surprised. I think when you find that, find out that I wrote that first manuscript, the complaints. Is my hearing of grievances if I Seinfeld preference? Yeah. I wrote that during, I wrote that in the second quarter of 2020. And you may recall that a lot of people had a lot of grievances and a lot of time on their hands in the second quarter of 2020.

[00:04:31] Oh yeah. Yeah. So that's what, yeah, so the, but the process of kind of thinking through it and really started to dig into this stuff was really 20, 19 and 20. I wrote the actual book that that wound up getting published. I wrote a lot of that in

[00:04:43] Leyla Gulen: 2021. Yeah. When you can say that the middle class has been shrinking for the last 50 years.

[00:04:49] I mean, as far as I can remember, people have been talking about the middle class and where is it going. But with all of that complaining, There has been such a lack of [00:05:00] solution this entire time. Why do you think that is? And why do you think today we're seeing such a change in our society with the whole advent of the trans movement and this very vociferous approach to getting that?

[00:05:19] Message heard. Why does it feel like we're getting traction on that front today than we were these last, this last half century when it comes to something so important as the middle class? Yeah.

[00:05:32] Chris Buskirk: Let me, yeah. Let me talk about the this middle class issue first because I think that's sort of the key to a lot of these questions.

[00:05:40] Or at least it's it at a minimum. I think it is a really good way to kind of. Understand the bigger questions. And so I, I would start from it this way and say like, the, a good way to understand what a, a vital and successful politics is, um, is, particularly for America, that's really [00:06:00] all I care about is one in which the middle class is demonstrably, like quantitatively self-sustaining, meaning it, it.

[00:06:09] Middle class families are able to produce middle class kids and grandkids. Now, they can go up or down, obviously based on their particular, their individual choices. But the point is that the middle class itself is a big part. It's like truly the middle. It's a big part of. Our society and it is one what that is prosperous.

[00:06:28] That and, and we have to define these things concretely, and this is like what I was kind of alluding to before, where political people tend to talk in platitudes, but I would say like the middle class needs to be able to do certain concrete things to define it, to be defined as prosperous. And that is a middle.

[00:06:46] You should be able to raise a family of four on a single median wage. You should be. And what could you, what should you be able to buy with a single meaning? One. So only one person in the family would need to work at it and [00:07:00] earn the median wage. Should be able to buy a house, buy a car, put your kids through school, have healthcare, maybe go on a vacation.

[00:07:05] Your basic, kind of the ideal of, I think what a lot of people think of as American. Middle class life. The reality is that it is the last time it was possible to do all of those things on one median wage in this country was 1989, and that had been the norm from about roughly the end of World War II until 1989.

[00:07:28] And since then, what's happened is that kind in the nineties, it took like one and a quarter, one and a half median wages, and then by the two thousands it took two median wages to do those things, which is, this is why you have. So many people where you have families where both mother and father, husband, wife, have to work, not choose to, but have to just to make ends meet.

[00:07:51] And that sort of distorts a lot of decision making and a lot of choices that people have. Do you know, do we have kids? Do we not have kids? How many of 'em do we have? [00:08:00] That sort of thing. And, and that is, I think that. That one statistic to me, when I learned that was true a few years ago, it just blew my mind because people want to, and I'm very sympathetic to this, people wanna say, well, something's going wrong in the country, and it's like a spiritual malaise.

[00:08:17] That's, I think that's probably true, but you know, as a political matter, you can't. You can't solve a spiritual malaise with like a bill in Congress, but there are things that you know that the political system can do, and one of the things is to try and make the country more prosperous. And so in order to do that though, you have to understand what you're, what are you aiming at?

[00:08:39] And so that's why I came, that's why I kind of in the book really leaned heavily into this metric and say, well, okay, the middle class needs to really be like, it's gotta be like 80, 70, 80% of the country should be defined as the middle. And on a one median wage, you should be able to do these very concrete things, but you know, it's a measurable outcome.

[00:08:57] And another factoid, just to under underscore, [00:09:00] this is in the top 25 cities in this country, there is not one of them where you can afford to buy a median priced house on a median wage in that city. Which kind of, that's, that's another one of these things that kind of like blows me away. It's like, so the average person can't buy the average priced house.

[00:09:22] Like how does that, like how does that even work? Yeah. And the answer is it doesn't. And some of the things that happen, and this goes to the other part of your question, laylo, about like, why do you have all these other sort of odd cultural things, movements happening? There's, I don't know the whole answer, but I do think part of that answer is that people redirect.

[00:09:44] Their energies. They basically are acting out their, some of their frustrations with what is effectively like a broken American dream, and they act those out and they find other ways to get some type of fulfillment or express the [00:10:00] frustration. And that's why you see in like you see the rise of all these different sort of political cultural movements.

[00:10:05] You famously, when you survey millennials over and over again, the millennials say like, they're delaying. Marriage. They don't want to have kids at a higher rate than any generation before. Millennials will say they don't wanna be married, then they don't want to have kids. Why? Maybe they really don't, or maybe it's just that they think they can't afford it.

[00:10:25] Like they've ingested that like down to like at a really basic level. It's like, Damn, I can't afford to buy a house, so I guess I'll just get like avocado toast and get, go to a festival and that'll be like a substitute like in San Francisco. Another like fun, fun fact. I used to live there. Yeah, I mean, San Francisco is one of the most, it's one of the most beautiful cities on the planet and it's been completely ruined, but more, literally more cats as pets in the city than there are children under 12.

[00:10:57] Leyla Gulen: I don't doubt it. I don't know how anybody can afford. I've [00:11:00] got friends who still live there and they are trying to raise their family. I don't know how they do it. I really truly don't, because I mean, just to get a parking ticket is like $75. The rent there is astronomical. The danger in the city has exponentially gotten worse since I left there in 2015.

[00:11:22] So it's not safe. It's not clean. And it's incredibly expensive. I don't understand how people make those ends meet.

[00:11:31] Chris Buskirk: Or why they want to. Like why they want to. Exactly. Yeah. I like, I do understand like if maybe if you've got like deep family connection there, you wanna stay with your family. Okay, fine. I get that.

[00:11:41] But like why would you voluntarily go there? It's like the quality of life is actually pretty low. It's like actually pretty dangerous. The culture's actually, I. Like pretty toxic. It's, and the thing about that Layla, is it didn't have to be that way, right? That, that was, that's the result of a lot of conscious decisions that were [00:12:00] made, both at the individual level and, and more importantly at the political level.

[00:12:03] Well,

[00:12:03] Leyla Gulen: and if this is vindicating for whatever side of the aisle you're on, I didn't interview with Carlos Santana born and. Raised San Francisco and that was fun. He can't, oh, it was fantastic. But he of all people can't understand what is happening to a city. He says it's unrecognizable. He said It's a horrible place now.

[00:12:24] And that Chris was in 2014 that I did this interview with him. Oh, wow. I mean, oh, that was a long time ago. So now we're looking 10 years later, practically, and it's only gotten worse. So, so with that in mind, okay, so, so you're saying that millennials today, and, and I think it's, some of it's a personal preference, but you're saying that there is this sort of anxiety of what the future looks like and their doubt that they can live up to sort of the standard that was set before them and [00:13:00] generations before them to be able to live up to those standards.

[00:13:02] So they're just acquiescing and just adopting cats and. Not really pursuing all the different things that life has to offer. It's,

[00:13:11] Chris Buskirk: yeah, it's like, but it's the water theory, right? The path of least resistance is the way it flows. And if you're a millennial at a very basic level, you understand the challenges that face this country because like you, like right in front of them.

[00:13:26] Like how do you start your life? I mean the, you'll the youngest millennials now are I think 27 or 28. They're at, they're so there are getting older, the Gen Z's coming up and is starting to face these things right behind them. It is like kind of how do you get, how do you get your life going? Like how do you get a job and kind of get established, get married, start a family, just like the basics of American middle class life.

[00:13:49] And what happened was, is like millennials really started to come of age in the great financial crisis, like in that era, like 2008, nine. Yeah. And they basically ran into [00:14:00] a buzz saw, right. And the G F C. And it was just like an acute manifestation of something that had been going on for a long time. If you look at household wealth, though, like the four major generations that are still alive, so the boomers, gen X, which is the next one after boomers, then the millennials, which is right after.

[00:14:22] Which is right after Gen X and then, sorry, silent Generation, which is the one before the, before the boomers. The boomers financially did better than anybody else. So, but what happens is, is you see, if you chart it out at every stage in life, The Boomers did the best, then the Gen X did not as well, has a, like, has a smaller share of national wealth than the boomers did at that.

[00:14:46] At any particular point in life, at 30 years old, 35, 40, 50, et cetera. And then the millennials did way worse. And the old millennials are now in their early forties, but they did way worse than Gen X. And Gen X had not done [00:15:00] as well as the boomers. Right. So the, so the millennials at 30 years old, or 35 are now 40, like they just have a much smaller share of national wealth than any of the older generations had at the exact same age.

[00:15:13] Well,

[00:15:13] Leyla Gulen: isn't that kind of ironic though, that the boomers did so well when they were also the ones that were propagating this ideal of freedom and expression and all of that, yet they were really reaping the rewards of the generation before them. And all the spoils that came after.

[00:15:32] Chris Buskirk: Oh, it's the ultimate irony of Layla.

[00:15:34] It's like these were, this was like, there's, they were counter-cultural and anti-establishment, but they, but the boomers literally just are the most establishmentarian generation, like, I don't know of the past century or whatever. They like, they flatter themselves. Like, oh, we went to Woodstock and like, we're like countercultural, like.

[00:15:53] They are just like the biggest conformists on the planet, and it's just like the ultimate irony because they're also like, [00:16:00] they're such salt flatterers.

[00:16:01] Leyla Gulen: Right. I've also heard them being mentioned as the most selfish generation in our lifetime.

[00:16:09] Chris Buskirk: I, I would say two things about that. It's that statement is true, and if anything it, it understates the case.

[00:16:17] There's such a great book about this by the way that came out, I wanna say 2019 maybe by a friend of mine named Helen Andrews, and it's called Boomers, and she's an elegant writer, but also like really did the kind of the social history, uh, of the boomers. It's like, it's a quick, really fun read, but it's just like so devastating, but it just puts the lie to all of the conceits

[00:16:38] Leyla Gulen: of the boomers.

[00:16:38] I'd love to read that and to speak about, just like you say, non-conformist. I mean, there were certainly out there, we've got plenty of. TV and video coverage of those days. When they were really celebrating the height of their expression. But you know, today we've got social media, so that is also a tool in which [00:17:00] our current millennials are propagating these other ideas, which tend, it seems like they're a distraction from really what's most important.

[00:17:08] So, so I'm curious, how do you get everybody kind of back on track and. Focused on what's important in life, our finances, our self-sufficiency, our education, all those things.

[00:17:24] Chris Buskirk: There's sort of two, there's kind of two answers there. The one of 'em is easier than the other. Neither are easy, but I would say it this way.

[00:17:30] There's, there's like the personal version of this, and then there's, and the answers there are what they've always been, which I'll say something about in a second. And then there's the national political civilizational version of that, which is, I think, much harder. The, the personal version is really always what it has been, which is like, do what you're supposed to do, like, just like personal discipline.

[00:17:51] Be focused. Work hard, tell the truth. Like literally, I mean, these are all cliches, but they're like, or they sound like it. I don't think they are, but it's like, do those things [00:18:00] like get married, like don't cheat on your spouse. Like, I mean, just the basics, like keep your family together. And if you do all of those things, like this is list is from all the complaints.

[00:18:11] This is really a great country where you can achieve a tongue. And in some ways, because some of the, some substantial portion of the country is so sort of like neurotic, sociopathic, like in a way if you just like kind of have your act together, like you can really, you can get ahead because those people aren't doing it.

[00:18:31] And that I, so I, I, I guess the, that's the personal version. But you still wind up the, those people who are doing what they're supposed to be doing and are kind of building their lives and they're doing well, they still wind up living in a society that is a little deranged and is, is kind of on, on the wrong trajectory.

[00:18:50] And so that's like, that's my bigger concern. That's the reason for the book. It's like, how do you fix those problems? And some of the things I, I proposed and full disclosure in [00:19:00] the book, like. I do not, I say this clearly, like I don't pretend like I, I have like the, like they say on the internet, one, solve these problems with one weird trick.

[00:19:08] Like I don't have that. Well, like what I proposed was to some things that I thought would be the start of solutions at a national like cultural. Level and always, I think that it comes back to giving people the, both the incentives and the, the, the room to experiment with solutions. And again, it comes back to an entrepreneurial mindset, but like one of the, one of the.

[00:19:35] One of the ideas that I put forward in, in the book is, and it's based on the like, kind of the, just the way people human nature is, but also on the kind of the history of this country as kind of a frontier country. It starts on the Atlantic coast and kind of pushes across the continent and is building the whole time.

[00:19:52] So we want to foster a culture that really incentivizes and permits building new [00:20:00] things. And so the proposal I put forward is to, is for states to. Allow what are sometimes called charter cities to be built and that they would basically ops operate with a substantial degree of latitude from a legal perspective to try and experiment with, with new forms of government, with business ideas, with to foster industry, innovation, these sorts of things.

[00:20:25] And I've given the talk about these new cities a bunch of times, and I always kind of have the same experience where there's like, There'll be like two people who are like, they've kind of heard of this before. And they're like, oh my gosh, that's so great. And they're like, the, everybody else is looking at me like I've got rocks In my head, they're like, you can't build a new city.

[00:20:41] Like that's the problem. You act. No, you can actually build a new city. That and that. It's if the states. Created a legal rubric within their borders where people could actually build a new city where they had a substantial degree of latitude on like the structures that, I mean, not just the [00:21:00] physical, but the like, the political and cultural structures that they built there.

[00:21:03] People would do it. It's that nobody's done it. The, the, actually the about, I guess it's five years ago or six years ago now, the governor of Nevada tried to do it in Nevada. Interestingly, he was a democrat and this is not an idea that Democrats typically like, but he like kinda led on it and he got absolutely like just had his legs cut out from under him by.

[00:21:25] His own party. And by the way, less, less people think that there's like not a precedent for this. There's actually a precedent. There are a couple precedents in our country and in history for doing exactly these sorts of things. Historically, in the Holy Roman Empire, there was three cities which operated, they, they were under the emperor, but they had a major, they had a really substantial degree of autonomy.

[00:21:47] Those became kind of like the Hong Kongs of the, in a certain way of the Holy Roman empire. They had, they were trading cities and they were very, they were really dynamic, vibrant centers of commerce and innovation. That's a historical [00:22:00] example, but even within our own country today, the two big examples are Puerto Rico, which is, it's a part of.

[00:22:07] It's a, it's, it is a part of the United States people that vote for President and so forth, and they operate under the US Constitution, but they don't. But they actually have a huge degree of autonomy and are, and have a legal structure, which allows them to experiment with different things, which for example, is why a lot of.

[00:22:25] A lot of crypto stuff has moved in the United States, has moved into Puerto Rico just because they created a legal system that permitted it and encouraged it. And so there's like that sort of experimentation. But the other, the other example in the United States where this actually exists is on the Indian reservations and people are, I think only in the past maybe 20 or so years had even had an inkling that this was true.

[00:22:49] But the reservations have, are substantially. Autonomous, not totally. They have their co, their Constitutional Protect protections, but they also have a lot of [00:23:00] self-determination. So the first thing that people did obviously was casinos, right? Because they were allowed to do it there. But there's been, just in the past five or 10 years, there's been other types of.

[00:23:09] Businesses that have moved onto the reservations that have made deals with the tribes that allow them to experiment with new sort of new types of businesses. And so if you take that sort of concept and you like to the next level and you say, okay, like here's this part of, I live in Arizona, here's this part of Arizona.

[00:23:31] We're gonna, we're gonna figure out how to just build something completely new. Like I think people, I think that would really just unlock a lot of the creative. Energy that Americans kind of naturally have. And again, that's another cliche about America's having like this natural, creative energy. It's totally true though.

[00:23:48] It is. I like we really do, again, for all of the sort of critiques I've got, this is the most dynamic place on the planet and there's a lot of things that Americans can do if they're just given [00:24:00] the space to do '

[00:24:00] Leyla Gulen: em. I think there's a lot of fire still in people in an that untapped fire as well, but there's plenty of people around that are trying to quell that, that are trying to extinguish it in order to create a world that, quite frankly, I don't understand, because when you're talking about the Democratic governor in Nevada wanting to create this kind of city within a city type of situation, we've got.

[00:24:25] Someone like R F K Jr. Who is despised by the Yeah. Extreme left. And so, so why is it that their voice is so powerful and why is it that there isn't sort of a match to try to right that ship in a back on a proper course? What do you think is the greatest threat right now to American greatness?

[00:24:49] Chris Buskirk: It's kinda like f d R said, uh, like a.

[00:24:52] Well, no, no, sorry, I was, no, I actually had that quote wrong. So scratch that idea. But like, the biggest item we have is ourselves, like the only, the [00:25:00] only way this country is being defeated anytime soon is by, is by ourselves. And what's that? That really is that, that kind of brings it back to the more concretely political, that's why these political.

[00:25:14] Issues are so important because it really is a choice between what's the direction of the country? Are we gonna be like a dynamic, innovative risk taking country, or are we gonna be one that kind of wants to, basically wants to smash everybody down. Anybody who pops their heads up gets leveled. This has always been, at least in modernity, like this really is the big.

[00:25:37] Political conflict between the leveling forces that just sort of wanna crush all, kind of, basically crush people under the boot of like this all encompassing state? Or is it, or is it a more free dynamic society where people are able to innovate and build a. Build a country worth living in. I, there's, I've got this phrase I use all the time.

[00:25:59] I say [00:26:00] like, it's, it applies in business, it applies in politics, but you know, you have to be, you, you gotta be always building. I say like, you have to build the country you wanna live in. And that's, that is always true. Yeah.

[00:26:11] Leyla Gulen: Yeah. Do you think we're too far gone and do you think we're too far gone that people are just going to acquiesce accept what is.

[00:26:23] Do you foresee your, with your own perspective, your own study and your crystal ball, that the tide is changing maybe, or could be changing in the next year or two?

[00:26:37] Chris Buskirk: I think, I think about it this way is, you know, the, that the expression you use, like about the tide, it's like every, everybody. It says, I think that speaks to the way we want to think about it as like the tide comes in and goes out of its own volition and I think there is definitely a cyclicality to, to societies, to politics, that that's definitely true.

[00:26:58] But I think [00:27:00] we kind of under index for. The importance of individual personal agency like the future is not predetermined it there, it depends on what we do. So I do not by any means think this country is, is too far gone at all. There's a lot of great people in this country, but we have to say, we have to really, I think, understand the present and the future is totally up to us.

[00:27:26] What are the deci, what are the things we're going to do? And we have to make that concrete. This is like why, this is why I did the book the way I did it. Like the second half of the book is, again, I don't think it solves everything by any means. I think it's just cer certain things that are big projects, but not, but they're doable and they're, and they're active.

[00:27:47] Like we have to take action to build the sort of world that we wanna live in. And if we do that, we can do it. I mean, think about. This really is the history of this country. You think about how [00:28:00] audacious every big project in this country has ever been. I mean, like how insane does it seem to be sitting in Europe in the, like the 16th or 17th century and say, I think, we'll, like, I think we're gonna, we're gonna cross the ocean in these basically little, little sailing ships that can hold a hundred people and like, let's go like, Let's go build a new civilization on the other side.

[00:28:23] Leyla Gulen: Yeah. Who death come, whatever, right. People, right? Yeah.

[00:28:26] Chris Buskirk: Oh, right. And then you kind of, you've kind, and they did it right? And then you kind of forwarded to the 18th century and they're like, yep, we're sick of, uh, we're sick of being ruled by England, and we're going to fight a war to start this new. To be able to create this new polity that, that got done.

[00:28:42] And then kind of after that it's like, we're a new nation, let's start building. And like we built like crazy. And then throughout the 19th century, the big American project was the frontier. Like, we've got this, we've got this massive continent, let's build. And I think that like we just have to really embrace that.

[00:28:59] [00:29:00] And the, what's happened is we, we, you know, our ancestors were very successful at that. They were. Major risk takers. Right. And I, I, I say like, what's the, one of the big forces against the success of this country is what I would call like sociopathic, risk aversion. Like, it's always like, and this drives me crazy since Covid, everybody says be safe.

[00:29:22] I. Stay sane. Like you don't wanna, you don't wanna take dumb risks. Like you don't wanna, like, I don't wanna stand in front of a train, right? Uh, but like life is risk. And if you try and avert too much risk, the irony is that it actually increases your risk. Like non-risk taking, society gets poorer. And that is, that's something we have to understand.

[00:29:42] It's like we need to be a risk-taking society if we wanna be able to push forward on like technological innovation or if we want to maintain our position in the world. If we want to maintain our, like our national security, our personal security, like those things all require risk and we need to just [00:30:00] like embrace a culture of smart.

[00:30:04] Aggressive risk taking.

[00:30:06] Leyla Gulen: Well, it sounds like in your book you have a call to action for folks that obviously they're gonna buy your book because they're already on that same page, if you will. But how do you then convince those who've been led down a garden path to then open their eyes and minds that might be contradictory to those false philosophies that they've been ascribing to in the last.

[00:30:28] Decade plus.

[00:30:29] Chris Buskirk: What I think when you're talking to people who maybe don't share the same like political view, this, my experience has been that when you sort of remove, and this is again, this is part of the reason why I, I wrote the book the way I did, but I did not want the book to be ideological. Like I there, like there, like I, there's a place for that, but there I have yet to find somebody when I say like, I think we need to find solutions to make the middle class like, Bigger, stronger, more prosperous, more secure.

[00:30:55] I haven't found anybody who's like, oh, Chris, I don't know. That sounds like pretty bad. Like, we [00:31:00] definitely don't want that. It's like it is a shared goal. And when I, there's a part of the book where I talk about, and because this, because like the what? Like health life expectancy in this country or total disaster, and it drives me totally like, it drives me crazy that that life expectancy has been dropping, that health outcomes have been getting worse.

[00:31:18] Like we spend more money per capita. On healthcare than any country on the planet. We spend way more than our peer countries, like in, in the O E C D, we spend way more than the uk. We spend way more than France, way more than Germany, and yet our health outcomes are way worse.

[00:31:37] Leyla Gulen: Okay. Yeah. And generally they've got a healthier lifestyle, particularly Germany, Scandinavia, those countries.

[00:31:45] Chris Buskirk: I look you, do you want, I'll blow your mind here. Compare the US to France about, if you wanna say, 15, 20 years ago, median life expectancy in both countries was roughly on par. Median life expectancy in France right now is about [00:32:00] 84 or 85. Median life expectancy in this country is about 75.5 years, and, and it's been declining.

[00:32:07] For a

[00:32:08] Leyla Gulen: ozempic is not the

[00:32:09] Chris Buskirk: answer. Ozempic is not the answer at all. It masks the problems and as we're finding out, it may cause other problems that are just now being revealed. But also you think about France, like their health outcomes late in life are better than Americans too. Heart disease is lower in France, like sort of the four horseman diseases, cancer, heart disease, dementia, diabetes, the per capita incidences late in life.

[00:32:33] In France are all lower than they are in the United States, and I'll blow your mind further. 35% of French are daily smokers, and yet they have four incidences of all of these diseases. Uh,

[00:32:46] Leyla Gulen: they can't have their cake and eat it too. Yeah. Is,

[00:32:48] Chris Buskirk: yeah, like, is the answer sitting just less of it drinking wine and smoking Marlboros?

[00:32:52] I don't know. It's worth of, don't forget the olive oil. That's right. That's right. But the point is like, that's something again, making like [00:33:00] our goals concrete like, like there's a part of the book where I call Project 100, like we should state as a national goal that people that the median life expectancy in this country 50 years from now is a hundred.

[00:33:11] Okay. Yeah. Like the Western European countries, France and Germany in particular. Also, you'd make a good point about the Scandinavian countries, like they're actually advancing towards that goal. We're going the opposite direction. Like that's gotta be turned around. And I, I think we're on the same page.

[00:33:26] If I, if I was picking up what you're putting down, but like the answer isn't just more drugs. The answer isn't just throwing more money at a broken healthcare system, like people like health is like a lifelong endeavor for everyone. It's not just like, oh, wait till you get sick and then go throw money at the problem at the Mayo Clinic.

[00:33:44] Like you. It's how you live and we can learn a lot, I think, from the communities around the planet. It's interesting with the Blue Zones that I think has some insight on this, but there's a, there we can learn a lot from the. Societies where people actually do live a long time [00:34:00] about like how do they live?

[00:34:01] Like part of it is what do you eat? How do you exercise? Part of it also is like there's a pretty high correlation between like family and community ties and longevity. In other words, there's the more sort of deep. Human connections you have with like your family, friends, whatever, maybe your church or whatever, that those people tend to live longer than people who don't have those relationships.

[00:34:23] Right,

[00:34:24] Leyla Gulen: right. And basically politically, socially speaking, I think a lot of times people are just allowing their inner voice to get drowned out by the noise that surrounds us. And I think the message and messages in your book should really open up people's eyes and. Some freedom in their life to, to come back to basics, to come back to what's important in life.

[00:34:51] Chris Buskirk: I hope so. I definitely hope so. I've gotten good feedback. So hopefully I, hopefully the book is helpful to people.

[00:34:57] Leyla Gulen: Well, that's great. And for people who want more information on the book and [00:35:00] where to find it, where do they go? Just

[00:35:01] Chris Buskirk: go, you just go to Amazon. It's called America In the Art of the Possible.

[00:35:05] Google my name Chris Busker, Googled the name of the book and there's a little, there's a sample there and or you could go to my publisher. They also sell it there. Encounter books. It's encounter books.com. I. Chris

[00:35:16] Leyla Gulen: Buskirk Publius fellow at the Claremont Institute, recipient of a fellowship from the Erhart Foundation and publisher, and a senior editor of American greatness.com, a leading voice of the next generation of American conservatism.

[00:35:30] Chris, thank you so much for joining us.

[00:35:32] Chris Buskirk: Thanks a bunch. This was

[00:35:33] Leyla Gulen: final. Absolutely. Thank you.

Alerts Sign-up

Alerts Sign-up